How a city copes with change, or copes with a crisis, will not just be determined by its plans and procedures, but by the strength of the relationships that have already been built. Planning a resilient city begins with building a strong sense of community. – Social sustainability policy and action plan 2018, City of Sydney

With flexible working conditions becoming the new norm, we will spend more time in our homes, our streets and neighbourhoods. To create resilient communities, we have to strengthen hyperlocal relationships in our neighourhoods. But there is a problem.

- Community engagement is one-off (e.g. specific public space upgrade) and doesn’t lead to community building.

- There are no effective, spam-free, safe channels for communication, collaboration and collective actions among community members, local orgnisations and businesses.

- Facilitators (e.g. local government) exit without an exit plan.

- Community champions overworked.

- No one is measuring and sharing the progress and impact of community investment real-time.

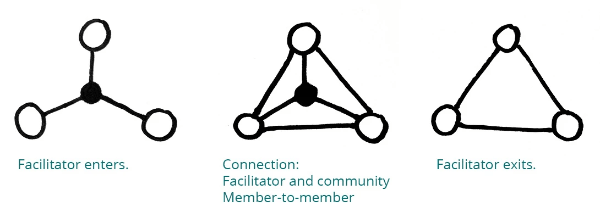

The building blocks of any community are relationships. At times of crises, we rely on those existing blocks to sustain our community wellbeing. As more place-related projects are being rolled out in Australia’s neighbourhoods, we must go beyond inviting people to ‘have a say’ in local projects. We must enable member-to-member relationship building.

That was the essence of the social enterprise Small Shift’s DIO (Do-It-Ourselves) projects. We used place improvement projects as a vehicle to build community resilience and social trust; and create employment pathways for people facing barriers to employment. The place activation projects were an impetus for the residents, organisations and businesses to collaborate, often for the first time. Some of the projects were more successful than others – and this depended largely on how strong the community ties were before the projects began.

![[The Small Shift Model] The diagram shows four areas of: Neighbourhood improvement; Meaningful employment; Social trust & connection; Civic leadership. They are all connected to a circle in the middle, which says ''everyone has the right to belong''. [The Small Shift Model] The diagram shows four areas of: Neighbourhood improvement; Meaningful employment; Social trust & connection; Civic leadership. They are all connected to a circle in the middle, which says ''everyone has the right to belong''.](http://custom-images.strikinglycdn.com/res/hrscywv4p/image/upload/c_limit,fl_lossy,h_9000,w_1200,f_auto,q_auto/1567257/255218_509759.png)

[The Small Shift Model]

Here is what I learned from working on projects ranging from #TacticalUrbanism and #CulturalPrecincts to #PlaceMeasurement and #Tech over the years that will help you optimise your investment in neighbourhoods.

1. Invest in community champions.

Community champions are motivated by their desire to serve the community, not monetary rewards. Their positive and inclusive attitudes earn respect from the community, however, they often lack structured support and ‘thank you’s, leading to excessive workload and expectation from the community. When the champion stops contributing, the whole community breaks down. It is critical to acknowledge their efforts and successes, support them with what they identify as their needs, and enable them to build relationships with each other and the community. On a one-off Small Shift project, we provided facilitation and project management services supported by a local council grant. Together with the community we delivered the project, but also really used the process to help the champion build on his existing network and contribution. He is now in conversation with the council directly about another project with no more support from us.

I learned a similar lesson while interviewing the Detroit Future City team. They ran a program that helped local residents turn vacant abandoned lands into working gardens, and in the grantee selection criteria was the strength of their existing community ties.

In some communities, there is no existing community champion and it takes a lot more time and effort to identify them and foster leadership. A series of small, simple community activities work better in this case, as the new champions can feel overwhelmed by big responsibilities.

Look beyond the most talkative people who may appear to be the champion type in the first glance. Those who may be less confident because of their age, personality, language or other barriers may need a little encouragement. They are also well positioned to share the experiences with their immediate networks who may be facing similar barriers and influence their participation.

2. Set up inclusive, sustainable channels.

Community building is about member-to-member relationships, not just the facilitator talking at the members. This means the local residents, businesses, organisations need a proper channel to communicate and coordinate actions. I say proper, because I don’t want anyone jumping onto Facebook without thinking about the ramifications. When choosing a channel/s, consider:

- Who regulates?

- I think of digital space in comparison with the physical. In physical public spaces, there are government regulations that determine how a space can or cannot be used. In publicly accessible private spaces, such as the forecourt of a shopping centre, the rules are different. Then, in the digital space, what are the rules? Who makes the rules? Are the rules conducive to community building?

Yet, consumers are also taking stronger actions to prevent the use of their personal data. According to Deloitte’s 2019 Privacy Index, 52% of respondents have used privacy enhancing applications and 89% have at some point denied an app access to location, photos, contacts, or other mobile phone features (e.g. cameras). – Deloitte, Mobile Consumer Survey 2019 – The Australian Cut

- How inclusive is the channel?

- Who misses out?

- How can the participants be grouped for effective communication?

- Who is accountable for the channel’s culture?

- Will there be hate speech, especially targeting at minority groups? This can impact people on the channel, as well as those who are not.

- How does it protect human vulnerabilities and advance humanity?

- Does it have a negative impact on our mental health?

- How does the channel support generosity and social cohesion, rather than merely enabling transactions of information, goods and services?

- What metrics are used to measure the outputs?

There are no perfect channels so this is a matter of identifying a good set for your specific community, rather than one-size-fits-all. This may be a mix of emails, messaging apps, doorknocking, (COVID-safe) regular face-to-face meetings and hyperlocal digital channels.

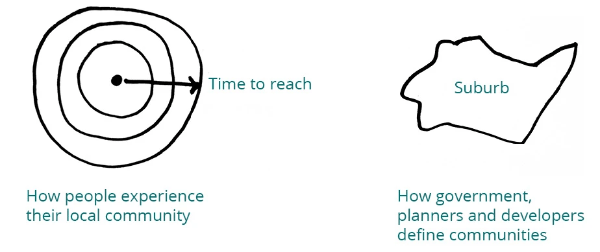

How should the community on the channel be organised? As government, planners or developers, it is natural to want to define the community boundary by the suburb or ownership. But people’s perception of place is more centred around them – let them choose what ‘community’ means to them.

3. Engage a facilitator, but have an exit plan.

While community champions are generous and empathetic individuals in general, they are still human and get along with some and not so much with others. They can also find it especially difficult to work in a divided community.

Some communities have champions who don’t get along with each other and won’t collaborate. Some champions feel stressed managing people as well as the project – unfortunately there are people who find joy in hate speech; some dominant voices can drive the project in one direction.

Sociological research has shown that the maximum 'natural' size of a group bonded by gossip is about 150 individuals. Most people can neither intimately know, nor gossip effectively about, more than 150 human beings. - Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens

Facilitators’ role is to be neutral and inclusive, and advocate community cohesion. They are not event managers who may be really great at delivering community BBQs and movie nights. The facilitator is an experienced moderator who can encourage and inspire the community champion to be more collaborative and inclusive, and support them with resources / regulations.

While engaging facilitators can help set the tone and jumpstart projects, it is important to have an exit plan. It should be made clear to the community that the facilitator is engaged for a specific time period and purpose; and they can together develop an exit roadmap.

The pandemic has highlighted social connection is the essence of our individual and community wellbeing. Let’s position construction stimulus projects so that they can deliver social as well as environmental benefits.