Pride was palpable in George Square as an eager crowd locked their eyes on the men and women magnificently dressed in green tartans, standing tall to play centuries-old notes. My visit to Glasgow couldn’t have been timed better. The city centre was bustling with Piping Live! and World Pipe Band Championships, bringing into the heart of the city uniquely Scottish tunes; deep, soulful and inviting a moment of reflection. Behind, elaborate details of Victorian emblems and statues on the City Chambers building and former General Post Office – the architects’ portrayal of wealth and status built about 130 years ago – added volume to the atmosphere.

It was a happy, sunny, festive kind of a day. But Glaswegians know George Square carries a meaning beyond festivity, it is a politically charged civic space. There, thousands had gathered for an anti-racism rally and marched against the Iraq War. Going back 98 years, in a riot called ‘Bloody Friday’, it was also where an estimated 60,000 people protested poor working conditions and wages and the Riot Act was read for the last time in the UK.

Glasgow was the backbone of the British Empire once, its growth peaking at the end of 19th century as a leader in industrialisation. Shipbuilding, machinery, textiles and tannery to name a few, contributed to the economic growth, and the city pulled through Scotland's Blitz during WWII. But with international competition and changing market went manufacturing jobs, and the merchant city’s decline began.

World Pipe Band Championships were held in George Square. On the left is City Chambers building and on the right former General Post Office.

The urban narrative

On the same day that I experienced the city’s grandeur in George Square, I also saw a city that never quite recovered from an economic decline. Its impact was felt in the derelict buildings, new developments tightly secured from the street and a public realm uncared for. Within five minutes, you could be shopping at Ted Baker on a bustling main street, then walking along a tagged wall with hostile metal fences and no one around. The city has big challenges: half a century of steep population decline, low voter turnout and volunteering rates, excess mortality, high unemployment and poverty rate with 34% of all children living in poverty. How do you shift a deep-rooted narrative of urban decline?

Since the 2013 launch (delivered in time for 2014 Commonwealth Games), the city’s slogan ‘People Make Glasgow’ attracted positive press as well as criticism for having a destination marketing focus rather reflecting the local values. Some Glaswegians didn’t mind having a good laugh about it though at their own expense. But perhaps the wording of the slogan is not as important as the meaning constructed by Glaswegians in the brand development and through its evolution. Today, #PeopleMakeGlasgow on social media shows diverse Glasgow identities and its promotional website claims: ‘Glasgow’s earned its reputation as one of the world’s greatest cities’. What does ‘great’ mean, for the locals?

New office and residential developments in the city centre are inward-looking.

Buchanan Street, one of the main streets with high-end shops, is bustling with shoppers.

Abandoned buildings with unidentified land owners dot the city.

Construction of meaning

Language is complex – what is said, how it is said, power relations surrounding the context, implicit meanings. The many facets of a city, communities and lives cannot be captured solely by statistics, yet numbers are considered to be more scientific and legitimate than language. Urbanists continue to produce rankings of places to indicate their success, yet they are based on a set of constructed metrics. Presented as simple and finite numbers, such rankings inevitably attract criticism from all angles. Just recently, there have been uproars about the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)’s global liveability survey, which Melbourne topped for the seventh consecutive year. Domain Liveable Sydney illuminated what liveable suburbs look like when liveability is seen through the lens of certain lifestyles that not many can afford. Will there ever be a perfect ranking system? No. But I think we can change the discourse of liveability, by shifting the focus from lifestyle aspirations for a few to communal well-being. In Scotland, this has begun to take shape in a structured manner, at a national level.

Holistic, inductive approach

The purpose of my visit to Glasgow was to learn more about Place Standard, a tool developed to explore the fundamental causes of inequalities and enable local action. Scotland’s health inequalities have been a priority concern for decades – Glasgow for instance, is doing poorly in every category from general health to long-term health issues and disability compared to the rest of the country. Recognising the link between health inequalities and spatial inequalities, three organisations got together. NHS Health Scotland , The Scottish Government (SG) and Architecture & Design Scotland (A&DS) developed ‘a framework for place-based conversations to support communities, public, private and third sectors to work together to deliver high quality, sustainable places’.

The aim is to use the tool to enable conversations centred on communal well-being. In a group setting, participants are invited to consider 14 categories that range from ‘influence and sense of control’ to ‘work and local economy’. Participants are asked to rank each category on a scale from 1 to 7 creating a visual snapshot and prompting discussions about their physical and social aspects. There is no attempt to arrive at final rankings here, and the NHS and SG teams are clear about why. This tool is not about comparing places or cities, it is about the community conversations and actions that follow them.

Meaningful participation

Improving people’s well-being is complex and cannot be achieved by a single-disciplined, short-term, top-down approach. Place Standard overcomes the fallacy of participatory research in urban planning at a time when many rely on a single set of data from pre-designed surveys. Participation in qualitative research refers to knowledge construction and the creation of meaningful content by participants – not ticking boxes on prepared questionnaires.

Place Standard’s big challenge now is analysing the data and putting it into use to influence national and city level policies. Challenging, because the quality of qualitative research depends on how well the research question is bounded; and transparency, reflexibility and generalisability of the research. This gets quite complicated when you start thinking about the data collection process at the local level: what’s the scale of the place, who’s facilitating and participating, who’s missing, are there any vulnerable groups negatively impacted by the process, how will the consents be managed, how will the data be captured, will the data be publicly available and how will it be secured and used? The facilitators’ role is critical in ensuring the quality of research stays high, as the co-constructed meaning will not only be manifested in written words and diagrams but also implicitly in the participants' interactions.

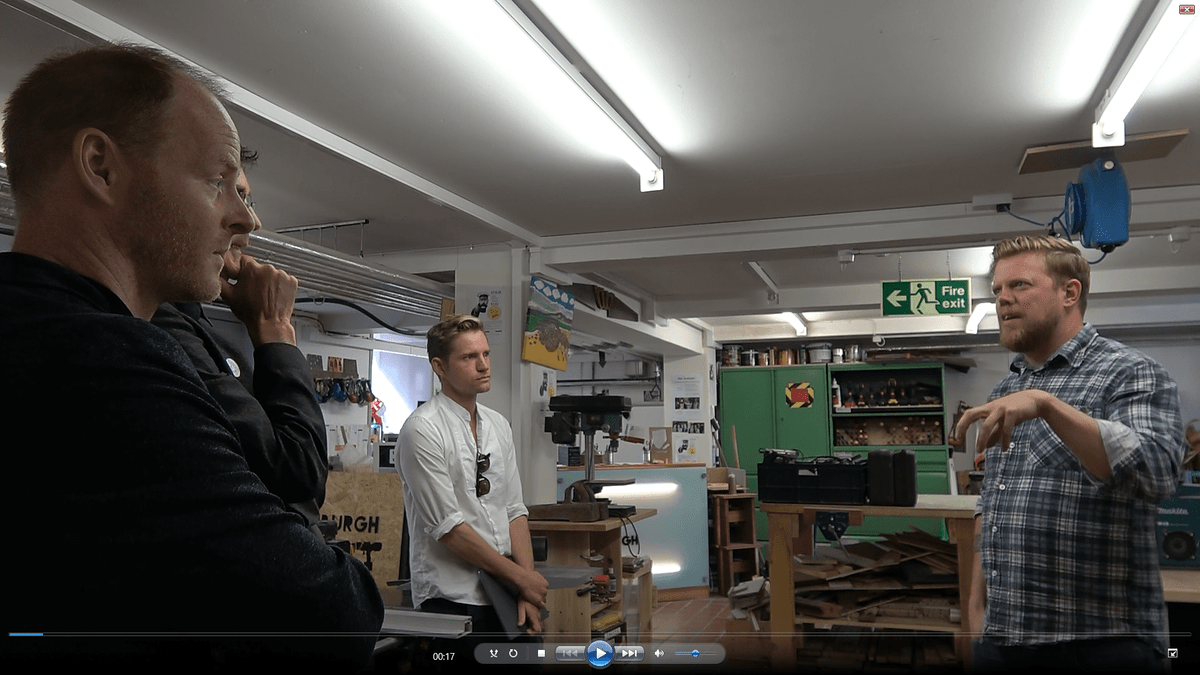

In Edinburgh, people are talking about the future of Leith, an area emerging as a new cultural hub driven by entrepreneurs, the government and citizens. (Where is Leith? Think Trainspotting) Leith Creative, a program being delivered by cultural organisations LeithLate and Citizen Curator, is one of the channels through which local conversations are taking place. Leith has suffered from years of inaction but its new image as a waterfront destination looks promising with the old Customs House getting filled quickly up with various creative organisations, since being reopened by GRAS. Edinburgh’s first Tool Library is also based there. The founder Chris Hellawell says one of its aims is to bring communities together in Leith, one of the most ethnically diverse wards in the country. Recent immigrants and established communities for instance, have the opportunity to mingle while making things in the workshop, rather than booking out the room separately.

Scotland’s aspiration to holistically tackle inequalities from different angles – private and public, health and space, local and national – is inspiring. Change won’t happen overnight. But it will happen with meaningful conversations.

Leith Walk connects Leith with Edinburgh city centre.

Leith Walk welcomes creatives.

Tool Library in the old Customs House offers opportunities for the local communities to connect.

Edinburgh Festival Fringe attracts all kinds of performers offering over 50,000 performances each year.

Many thanks to these organisations:

This blog post was made possible by Westpac Social Change Fellowship, during which Julia Suh is visiting 15 cities to learn from their governments, social enterprises, consultants, academics and community organisers about how they are addressing inequality via design and management of the public realm and bringing about positive change.