“In going up St. Peters Street & approaching the Common I heard a most extraordinary noise, which I supposed to proceed from some horse mill--the horses tramping on a wooden floor. I found, however, on emerging from the houses to the Common, that it proceeded from a crowd of five or six hundred persons assembled in an open space or public square. I went to the spot and crowded near enough to see the performance. All those who were engaged in the business seemed to be blacks.” (Excerpt from Benjamin Latrobe’s notes -- see full text here page 33-34)

This 1819 description of a public space by architect Benjamin Latrobe, is one of the earliest accounts of jazz and the evolution of African music and dances in New Orleans. Under the Catholic Spanish and French rule, African slaves were allowed take Sundays off, and would gather in the open space to beat the drums, play string instruments, dance and freely socialise. The name, use, users and political context of the space changed over time, and included being named Beauregard Square in 1893 after a former Confederate General. The City of New Orleans renamed it Congo Square in 2011. (If in New Orleans, visit The Historic New Orleans Collection to learn about the city’s complex history.)

“Public space in New Orleans may be the opposite of design,” says Jared Genova, Resilience Planning and Strategy Manager at the City of New Orleans (the City), citing various social episodes that appear spontaneously in places that weren’t designed for that purpose. For him, resilience means creating everyday social and economic opportunities, and goes beyond the hype of post-Katrina disaster readiness. Over my three-day visit his remark turned out to be fair, as I would often observe locals hanging out on the front porches, the musically talented jamming on the streets and young people skateboarding below interstate highway overpasses. In this city, design of the public realm is often facilitated based on the locals’ organically developed use of the place, driven by the user groups themselves and/or the City. Such manner of planning has presented different kinds of success indicators. In neighbourhoods where resources are limited, there may not ever be a perfect concept design, a completed project or a refined sense of materiality. Instead, there is genuine and resilient DIY spirit emerging from people who desperately want a common ground where they can just, be.

One of the earliest accounts of the evolution of jazz refers to Congo Square.

An impressive 8-person band draws a large crowd at Jackson Square, the heart of French Quarter.

Tourism is one of the main industries in New Orleans.

Active citizens

To see this spirit in action, I paid a visit to a DIY skatepark under an overpass, created initially by a group of skaters who literally made concrete walls and ramps on site. It was illegal and got knocked down. Disappointed, but unwilling to let go, they built a much better and bigger second skatepark. It also got knocked down. Their response? They formed a not-for-profit and successfully negotiated with the City for it to be formally designated as Parasite Skatepark. Tulane School of Architecture students stepped in and designed the next phase through various collaborative workshops.

Arts Council New Orleans’ Youth Solutions program guides young people to take ownership of their own neighbourhoods and implement improvement projects. Its impact lies in helping youth overcome anger, powerlessness and helplessness associated with trauma, with creative placemaking projects. Paid practical internships such as carpentry and welding, as well as mentorship, are available. The program has seen young people learn to empathise with the needs of younger kids and create a pop-up park for them; build seating for public spaces; and interview locals for asset mapping.

Parasite Skatepark is well used by the locals.

Under the concrete slabs of overpasses are playgrounds and other types of gathering spaces. On hot summer days, they offer some respite from the heat and humidity.

Go to where the people are

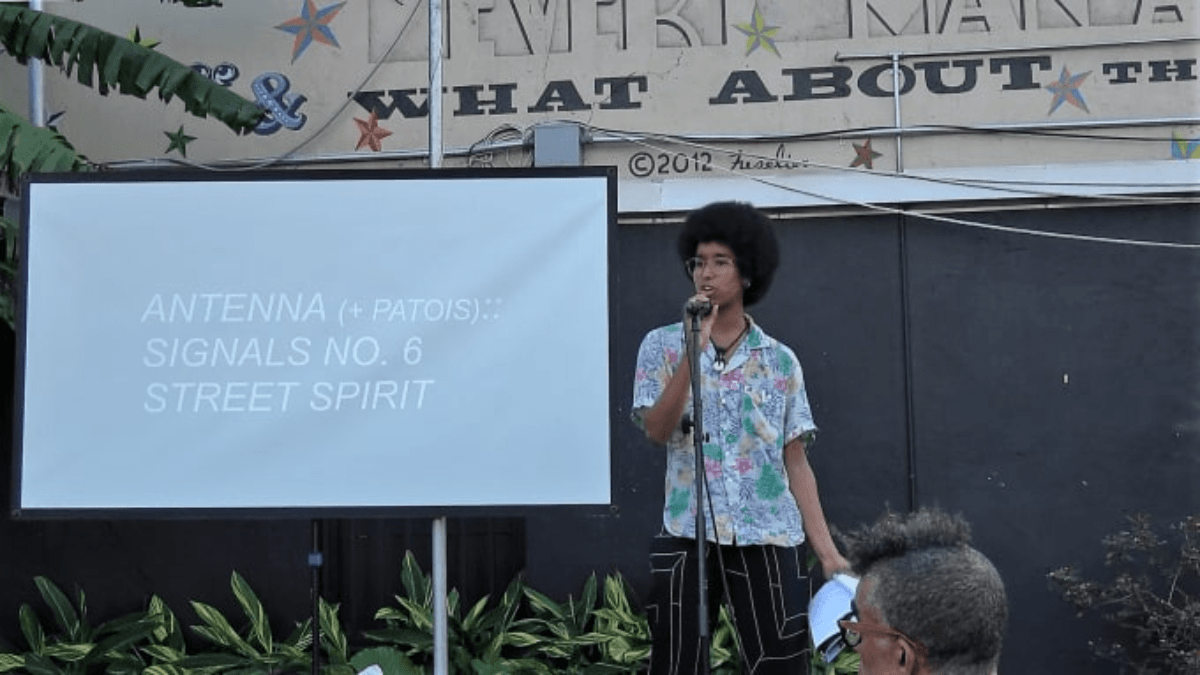

For activists like Imani Brown, founder of Blights Out and director of programs at Antenna, supporting active citizenship means creating a space where dialogue can be generated and art can make the streets its home. I get a sense of what that might look like at an event held in a bar, Street Spirit, where Imani aims to bring “artists, activists, scientists, spiritualists etc who come from a myriad of different backgrounds but whose work intersects in a way that is unexpected and hopefully is delightful and engaging”. The event is a mix of music, talks, poetry, and surprisingly a presentation by a Certified Floodplain Manager explaining New Orleans’ urban planning and flooding history, and micro-scale stormwater management solutions for the individuals in the audience. Raising awareness on hazard mitigation starts here, where the people are.

Imani tells me about the many prejudices, systems and laws that have taken a toll on New Orleanians’ lives: the Brown Paper Bag test, which was used to determine the status of a person of colour based on the skin colour (and colourism still exists); the loss of free public spaces when the beaches and pools were closed to African Americans; and most recently, a segregated school system that is further suffering from the replacement of ‘veteran black educators’ following Katrina. ‘Integration’ is a politically charged word especially in New Orleans, where hundreds of years of unjust systems continue to influence and segregate its communities. Imani would like to see more places where different people feel the invitation to connect.

A diverse group of people gather in the back of a music venue for Street Spirit.

Imani Brown opens Street Spirit and brings together artists, activists, scientists and spiritualists.

Learning from the neutral ground

When the newer American residents and French-speaking Creoles began to cohabit the city in 1800s, their quarters were separated and demarcated by Canal Street – Americans to the west, and Creoles to the east in the French Quarter. The area of demarcation was thus known as ‘the neutral ground’ and the term has been generally used to describe all median strips in the city since. Neutral grounds today are where people socialise, walk and rest (and where people can park to prepare for flooding). Melissa Lee, Senior Advisor for Commercial Revitalization at New Orleans Redevelopment Authority (NORA), wants to see the celebration of inclusion continue on these grounds. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, for instance, has a neutral ground, which will be improved to signify the social justice history and connect the local community. Following the public spaces where people already are, NORA is also working on creating an ‘edible walking trail’ for a neighbourhood, where its older people tend to walk up and down the street for exercise, and the culture of community gardening has evolved into urban farming. It is hoped that the loop encompassing African, Vietnamese and Latino communities will lead to unexpected and positive cultural exchanges and community cohesion.

Public spaces in New Orleans could have been left empty, and neutral grounds stripped off any character or sense of ownership. Instead, New Orleanians – whether they are old Vietnamese gardeners or young African American students – are finding ways to manifest their values in the public realm. As the City develops strategies to overlay water infrastructure with public spaces, I imagine this culturally unique city could also prove to be the most technologically innovative and socially inclusive.

Canal Street used to separate the newer American residents and French-speaking Creoles.

French Quarter is human-scaled and beautifully maintained.

Street signage on the footpath is often seen in neighbourhoods.

Many thanks to these organisations:

This blog post was made possible by Westpac Social Change Fellowship, during which Julia Suh is visiting 15 cities to learn from their governments, social enterprises, consultants, academics and community organisers about how they are addressing inequality via design and management of the public realm and bringing about positive change.