Layers of mismatching blankets and a fluffy white pillow are placed gently on a thin single mattress, pushed against a vacant, but handsome, building in Darlinghurst. The former substation and toilet building in Taylor Square has a palpable public presence – with all four sides wide-open, and the site un-programmed and unclaimed. The permanence of the brick building, now about 112 years old and heritage-listed, is starkly juxtaposed with temporariness of the mattress. Ordinarily a representation of warmth and intimacy, it is left cold and exposed.

Who placed it there? Who will be sleeping in it? Is it art? A protest?

Or the state of our citizenry decency?

Former substation and toilet in Taylor Square

It is 7pm on a Friday. Bars, restaurants and clubs on the connecting Oxford Street are just warming up toward end-of-work celebrations, inviting people in from the night chill. The public spaces are quickly filled with a dominant class: local residents and visitors with disposable income, stimulating the night economy.

Public spaces attract planned and incidental interaction, increase economic activity and build social trust. They are also places of disorder, expected to be administered by what constitute as social norms. The unease aroused when approached by homeless people on the street, or when our personal and public spaces have been compromised – prompts the question who has the right to the city and public spaces?

Citizenry engagement of the socially excluded is still underdeveloped and under-practiced in neighbourbood planning. Many of them – including asylum seekers, refugees and the homeless – have no first place (home) or second place (work) to be in. The third place (public space) is thus appropriated as all three.

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody”, said Jane Jacobs. But how far should we go? How do we invite everyone to co-create our cities? Is this an idealistic vision of a socialist, which our market economy simply cannot and will not support?

Of the community engagement activities I have delivered across diverse Australian cities, participation patterns have common themes: those with resources – whether it is time, money, health, education or cultural advancement – will be better heard; those without, won’t. And the poverty of opportunity will continue in a vicious cycle.

I have been spending a bit of time with the street community in Darlinghurst, to co-design and co-deliver public domain improvements for a community cafe. A refuge for the homeless, Rough Edges serves meals and provides a safe place for the street community to socialise. Located amidst Darlinghurst’s vibrant restaurants, bars and cafes, its public domain is, in contrast, apologetic, deteriorating and hides away from the public.

The biggest challenge that I set up for myself is to sustain the energy from the engagement stage and empower the community to be upskilled in the process of change. To build true ownership of shared resources or spaces, the user groups need to be involved from the beginning to the end – that is, from defining the problems and ideation, to prioritisation and delivery.

Interviews with the community, volunteers and local businesses, site audits, and a workshop were carried out. The participants were especially enthusiastic about painting a mural -- creating artwork as a representation of the community with spots available for people to fill in with the portraits of themselves, their families, things or pets. With 6 people who have already put their hands up to co-deliver the project, this public domain will soon offer a sense of belonging to those that have nowhere else to belong to but in the third place.

Stephen Corry, an artist and a regular at Rough Edges, is all too familiar with how that works. “If you include as many local people as possible in the painting process, they will protect the wall”, he says as he pulls up a large black folder filled with his sketches, prints and paintings. The bold, at times confronting, themes oscillate between safety and warmth, and survival and fear. The man is talented. He could teach the rest of us how to prepare a wall, paint and look after murals (check out his upcoming exhibition). Sitting quietly next to him, a young man shyly puts forward a canvas, covered in elaborately painted typography. “I can spray paint”, he says. I am elated with possibilities.

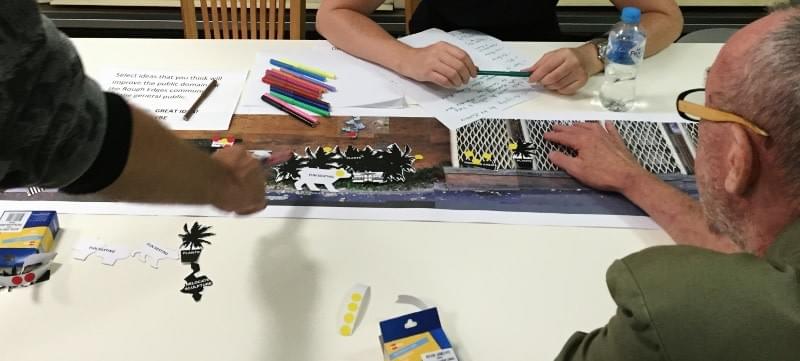

Participants discuss priority implementation ideas at the Rough Edges community workshop.

As much as Rough Edges is a place for the street community, the project is also about giving back to the local residents and visitors. The workshop participants liked the ideas of a community book share, child-friendly playable area and more seating for the general public. Currently an average of 222 people walk by during the day/evening and 30% of the children can’t help themselves but to play on the wall in the front.

Co-creation and partnerships started to form, as our story began to take shape and be shared. This project is not only a public domain improvement project, but a means to upskill the participants in the process of change. Stephen’s knowledge and skills in street art will be shared with the community. Local businesses are looking forward to the change and continue to offer in-kind support. GoGet has generously donated a workshop session for a volunteer to build a Street Library, to be painted by the community and installed onsite.

A sense of purpose, fulfilment and meaning of life – these aren’t the needs reserved only for people with money. Any opportunity to empower marginalised people to achieve self-actualisation and esteem, must be rigorously and actively taken. Learning a new skill (e.g. painting, carpentry, landscaping) and demonstrating the ability is a good start. In turn, the property will be protected by these ‘guardians’.

The right to the city of some at times challenges the rights of others. It gets people angry at times. But until the marginalised people are standing just as close to an array of opportunities as the rest of us, tents, mattresses and personal belongings in our shared space deserve kinder eyes.

UPDATE: This project was implemented in 2017 and this video shows the outcome and impact.